The State of Bicknell’s Thrushes

Regionally: Declining

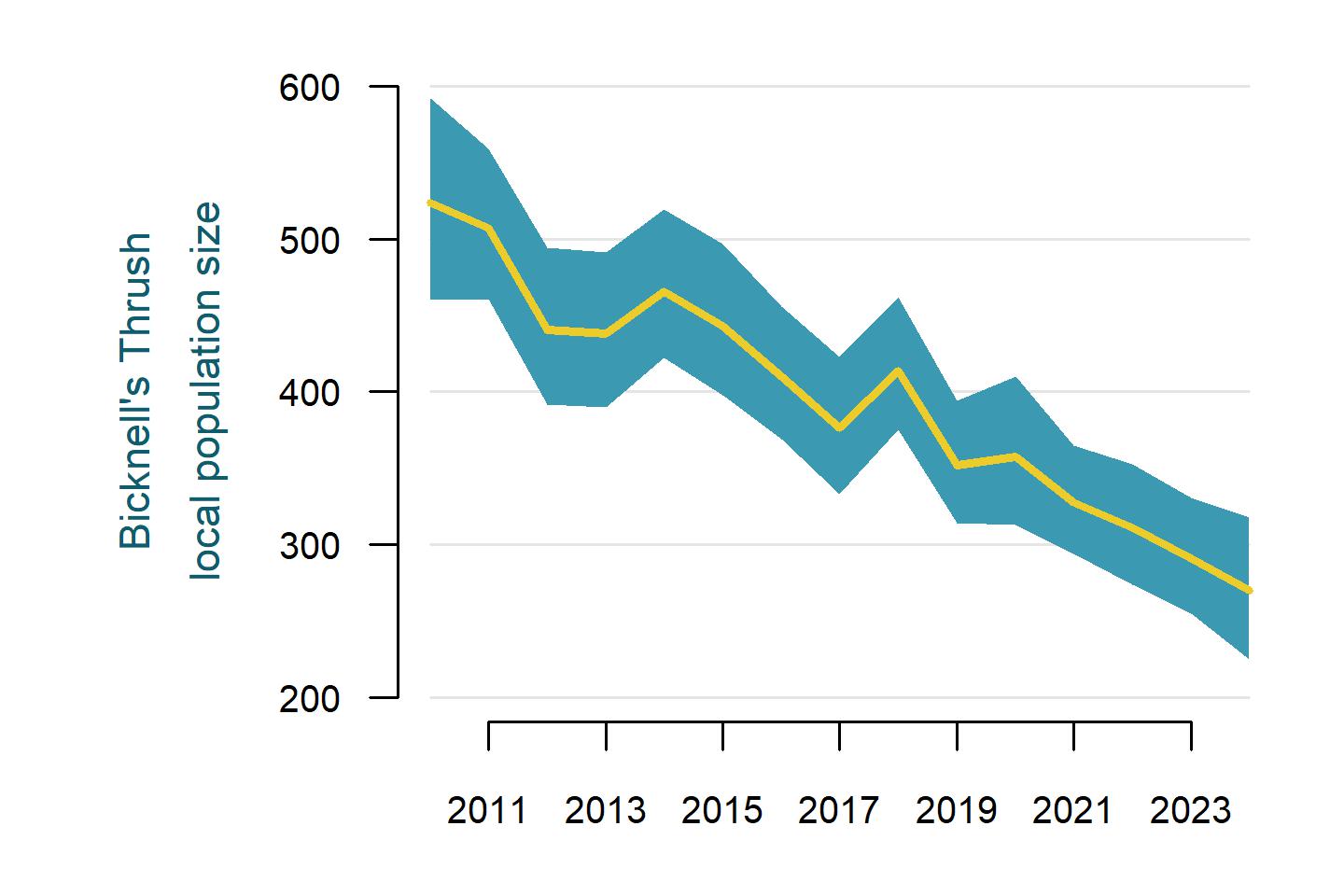

The mean (thick, yellow line) annual estimate of Bicknell’s Thrush abundance within the immediate area surrounding all 803 Mountain Birdwatch sampling locations, with a 95% Bayesian credible interval (blue polygon, representing estimate uncertainty).

Mountain Birdwatch data suggest that Bicknell’s Thrush populations have declined by an average of 4.63% per year in Northern New England and eastern New York over the last 15 years. Expectedly, the region-wide figure above somewhat masks the trends that are occurring at the state level. Bicknell’s Thrush populations are declining the least in the Adirondacks and Vermont, with the steepest declines occurring in the Catskills where this species has decline by ~65% since 2010. If that rate of decline continued, it is possible that we would observe a population decline of greater than 95% in the Catskills by 2050. The Catskills, however, likely harbor less than 5% of the U.S. Bicknell’s Thrush population.

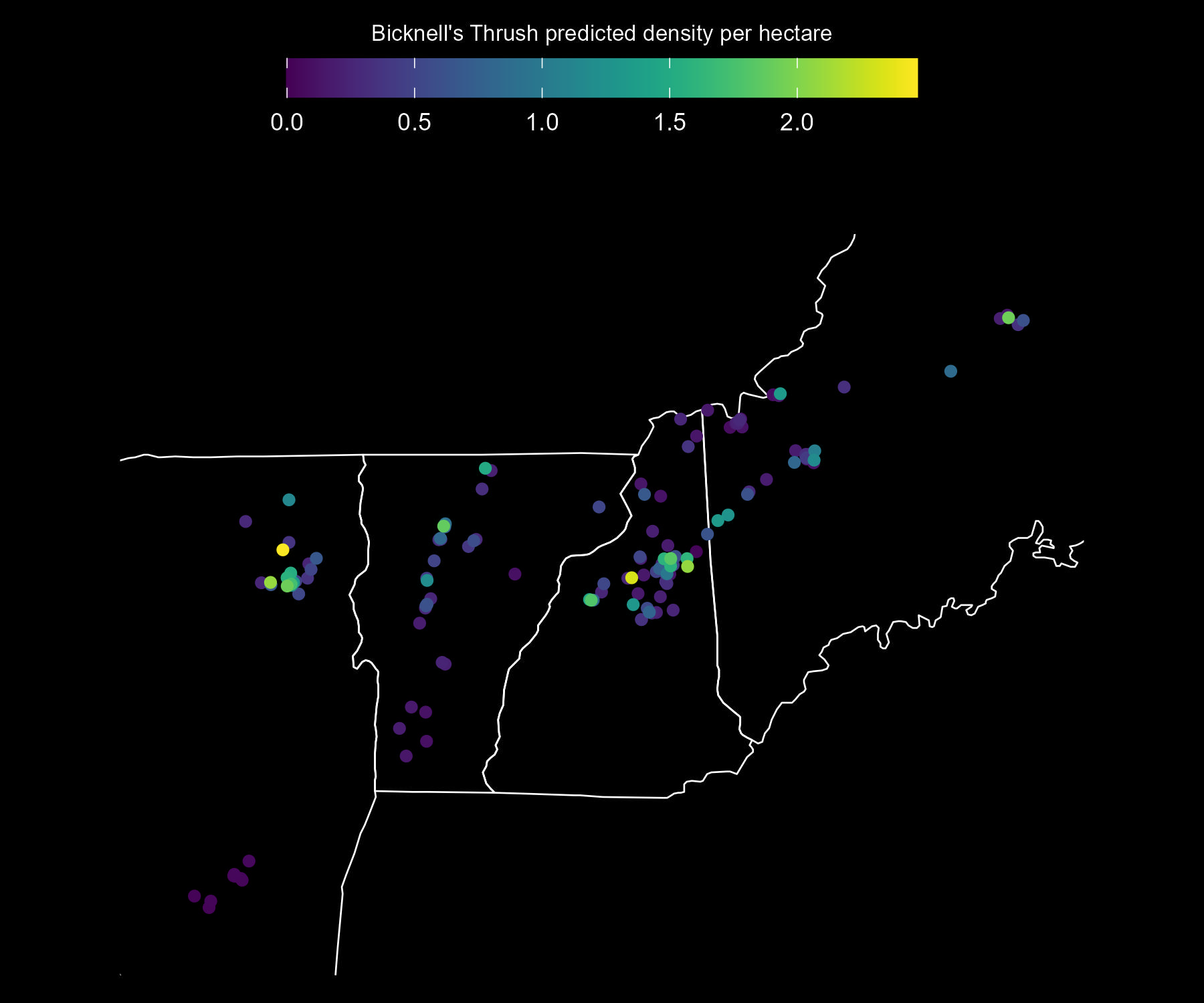

Predicted Bicknell’s Thrush adult density per approximate hectare in an average year (between 2010 and 2024), as estimated from Mountain Birdwatch data. The base map shows the extent of the Mountain Birdwatch region: eastern New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and western Maine.

| Region | Mean annual trend (%) | Trend (80% CRI) | Probability of decrease | Probability of increase | Population change (%) 2010-2024 | Population change (80% CRI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All regions | (-5.55, -3.69) | >0.99 | <0.01 | -48.48 | (-55.07, -40.91) | |

| Maine | (-6.42, -3.45) | >0.99 | <0.01 | -50.81 | (-60.49, -38.87) | |

| New Hampshire | (-7.17, -4.68) | >0.99 | <0.01 | -57.41 | (-64.73, -48.86) | |

| New York (entire region) | (-5.42, -2.50) | >0.99 | <0.01 | -43.33 | (-54.17, -29.81) | |

| New York (Adirondacks) | (-5.15, -2.02) | >0.99 | <0.01 | -40.25 | (-52.30, -24.86) | |

| New York (Catskills) | (-9.42, -5.15) | >0.99 | <0.01 | -65.12 | (-74.98, -52.32) | |

| Vermont | (-2.75, -0.05) | 0.91 | 0.09 | -17.69 | (-32.29, -0.73) |

Globally: Likely Declining

Mountain Birdwatch data accurately tell the story of Bicknell’s Thrush population health in the northeastern United States. But to understand the global state of Bicknell’s Thrush, we also need to consider data collected in Canada, which is home to a significant number of Bicknell’s Thrush. The Mountain Birdwatch sampling protocol formerly extended throughout Canada, but Bicknell’s Thrush populations tend to be ephemeral in the northernmost part of their range. In other words, Bicknell’s Thrush may be locally abundant in Quebec during one year, but largely absent the next year (and locally abundant someplace else) – a boom and bust population dynamic not uncommon for local populations on the edge of a species’ geographic distribution. The Mountain Birdwatch sampling protocol (i.e., surveys at fixed locations every year) is not an ideal sampling methodology for this ephemeral scenario. Two-stage or cluster sampling would be a better strategy for the population dynamics of Bicknell’s Thrush in Canada, and indeed, our colleagues in Canada have considered moving in that direction.

The North American Breeding Bird survey (BBS; which samples fixed locations along roadways every year) does not adequately sample (the largely roadless) spruce-fir montane habitat. As such, the BBS trend estimates for Bicknell’s Thrush are uncertain and not available for the entirety of the breeding range. That being said, the BBS trends suggest a decline of between 2% and 3% per year, but the number of survey routes on which Bicknell’s Thrush are detected is small and thus confidence in Breeding Bird Survey results is low. However, the second Breeding Bird Atlas of the Maritime Provinces shows recent local extinctions of some coastal populations in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, which also supports the idea that overall numbers of Bicknell’s Thrush are dwindling. This pattern is similar to research from other animal and plant systems which finds that peripheral populations tend to become extirpated (locally extinct) first when that species is globally declining. eBird trends are also highly uncertain for much of the breeding range of Bicknell’s, but suggest that Bicknell’s Thrush have declined by as much as 30-60% over the last decade in Eastern Quebec.

The U.S. Bicknell’s Thrush population was estimated to be 71,318 (95% credible interval: 56,080–89,748) in 2016 (source: Jason Hill and John Lloyd’s 2017 Ecosphere paper). Combining those results with existing estimates of population size in Canada suggested a global population size of <120,000 in 2016; Bicknell’s Thrush likely have one of the smallest population sizes of regularly occurring bird species within the contiguous United States and Canada. Given our observed declines since 2016, it is likely that the Bicknell’s Thrush population within the United States has further declined to approximately 50,000 in 2023. At current levels of warming (and associated changes to moisture regimes), we can expect more than half of the existing Bicknell’s Thrush breeding habitat (spruce-fir forest) in the northeastern U.S. to be replaced by the upslope movement of hardwood forest communities within the next 200 years, further decreasing their population.

Conservation Actions

The International Bicknell’s Thrush Conservation Group outlines a complete discussion of the threats facing Bicknell’s Thrush in the updated Conservation Action Plan for Bicknell’s Thrush.

- Address climate change caused by our activities by supporting government policies and making individual choices that lead to a reduction in greenhouse-gas concentrations.

- Conserve breeding habitat

-

- Breeding habitat in the United States are already largely conserved; Hill and Lloyd (2017) estimated that 85% of Bicknell’s Thrush in the U.S. occur on conserved lands like national forests and state-owned conserved areas.

- Breeding habitat in Canadian forests should be conserved by making sure that best-management practices for forestry operations are adhered to whenever logging occurs in areas inhabited by Bicknell’s Thrush (many Bicknell’s Thrush in Canada occur in forests undergoing timber operations).

- Development in mountain-top breeding areas should be avoided wherever possible.

-

- Conserve wintering habitat.

-

- Winter habitat in the Caribbean should be protected by purchasing it and permanently setting it aside for conservation, by developing easement agreements with willing landowners, or by supporting compatible land uses that provide economic returns while protecting the forest ecosystems required by Bicknell’s Thrush.

- These are obviously complex issues, involving both local and global economic processes, but our colleague Yolanda (Yoli) León is tackling these difficult conservation issues in the Dominican Republic.

- A great case study for integrating conservation into sustainable development is Reserva Zorzal, a farm in the Dominican Republic where seventy percent of the land is set aside to provide habitat for Bicknell’s Thrush and the remainder is used to grow cacao, which generates revenue and jobs.

- Winter habitat in the Caribbean should be protected by purchasing it and permanently setting it aside for conservation, by developing easement agreements with willing landowners, or by supporting compatible land uses that provide economic returns while protecting the forest ecosystems required by Bicknell’s Thrush.

-