Population Size and Habitat Requirements for Bicknell’s Thrush

Scientists from the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE) – Dan Lambert, Kent McFarland, Chris Rimmer and Steve Faccio, along with colleague Jon Atwood – used data from the early years of Mountain Birdwatch to document the habitat requirements of Bicknell’s Thrush. For the first time ever, these scientists were able to quantify the type of forest that Bicknell’s Thrush used for nesting. In doing so, they provided valuable information to land managers and conservation planners tasked with evaluating the environmental impacts of development in the high mountains of the northeast.

Mountain Birdwatch data were also used to identify particular features of mountain forests that are important for Bicknell’s Thrush. Sarah Frey, from Oregon State University, Allan Strong of the University of Vermont, and VCE scientist Kent McFarland found that Bicknell’s Thrush needed not only suitable habitat – dense stands of short balsam fir with many dead trees, both fallen and standing – but that habitat patches needed to be large and widely distributed across a mountain. In other words, conserving Bicknell’s Thrush means maintaining many large patches of suitable habitat.

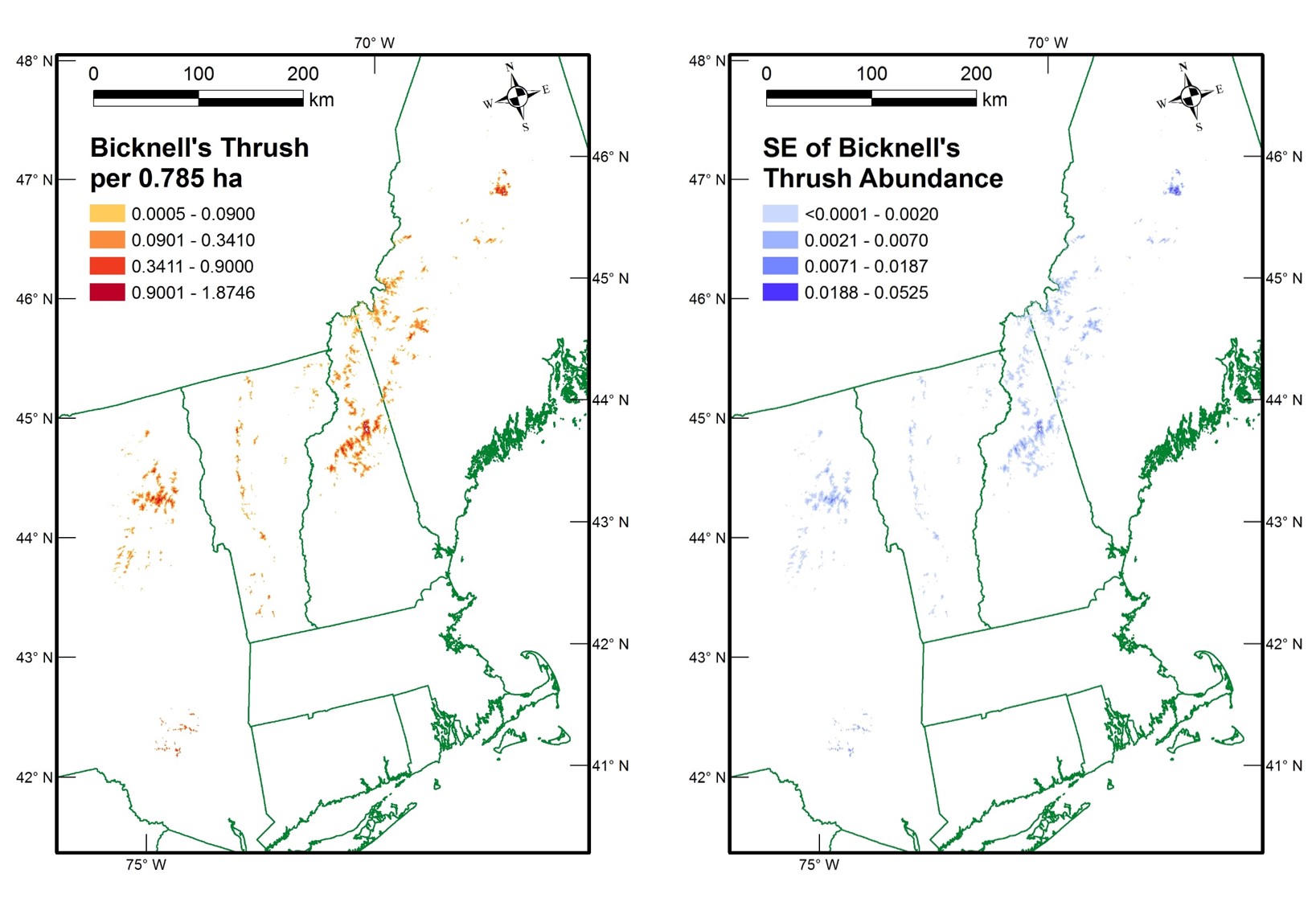

More recently, VCE biologist Jason Hill and former VCE biologist John Lloyd used those habitat models and Mountain Birdwatch data to produce the first fine-scale (<1.0 ha resolution) abundance estimates for Bicknell’s Thrush across their U.S. range. Hill and Lloyd predicted the U.S. Bicknell’s Thrush population in 2016 as 71,318 (95% credible interval: 56,080–89,748), and 95% of that population occurred above 805 m. Combining those results with existing (rough) estimates of population size in Canada suggests a global population size of <120,000. Thus, Bicknell’s Thrush likely have one of the smallest population sizes of regularly occurring bird species within the contiguous United States and Canada. By cross‐referencing the U.S. Geological Survey Protected Areas Database, we estimated that 76.6% of Bicknell’s Thrush habitat occurred on conserved lands (e.g., national and state forests) across the United States and that this habitat supported 84.6% of the predicted population. The White Mountain National Forest (New Hampshire and Maine) is the largest conservator of Bicknell’s Thrush habitat in the United States and supports ~31% of the predicted U.S. population. These results provide even more actionable information for land-use planners and those interested in conserving key habitat areas for Bicknell’s Thrush. To encourage wide use of the results, we make the Mountain Birdwatch data open and available to everyone.

Fine-scale abundance (left panel), and their uncertainty (right panel; SE = standard error) of Bicknell’s Thrush across the U.S. breeding range in 2016. Darker colors indicate greater density (left panel) or uncertainty (right panel) of Bicknell’s Thrush. The inset in both panels shows the Katahdin area of Maine. Figure from Hill and Lloyd (2017; https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1921). You can download or interact with this map at https://databasin.org/datasets/abc7ade46ed7444788b4d3d167293236.

Protecting Mountain Landscapes

Multiple land trusts have relied on Mountain Birdwatch data to identify important areas for conservation in the High Peaks region of Western Maine and in locations across Vermont. For example, in 2013, The Trust for Public Land purchased 12,000 acres at Crocker Mountain – now owned by the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands – to help protect high-elevation forest habitat for our montane bird community. The area is now an ecological reserve, in large part due to its importance as breeding habitat for Bicknell’s Thrush and other mountain birds. The value of this area as an intact block of habitat for birds of the spruce-fir forest would not have been known without the data collected by Mountain Birdwatch.

In Vermont, The Trust for Public Land conserved more than 2,000 acres adjacent to Camel’s Hump State Park in Vermont based in part on the value of the area as breeding habitat for montane birds, and is currently using Mountain Birdwatch data to identify conservation opportunities in the Worcester Range of central Vermont.

Identifying Species At Risk

A good example of a broad application of Mountain Birdwatch data comes from a recent research paper that examined population-trends for bird species that nest in spruce-fir montane forests. Using Mountain Birdwatch data, Joel Ralston and his colleagues documented population declines among species that depended on mountain forests for breeding habitat. In the words of the authors, the results of this study “confirm and extend species-specific conservation concern within the spruce-fir forest community and identify species for which additional attention may be needed”.

Have you used Mountain Birdwatch data to help promote conservation of mountain birds and their habitat? If so, let Jason know () know!