The State of Red Squirrels in the Northeast

Regionally: Pulsating

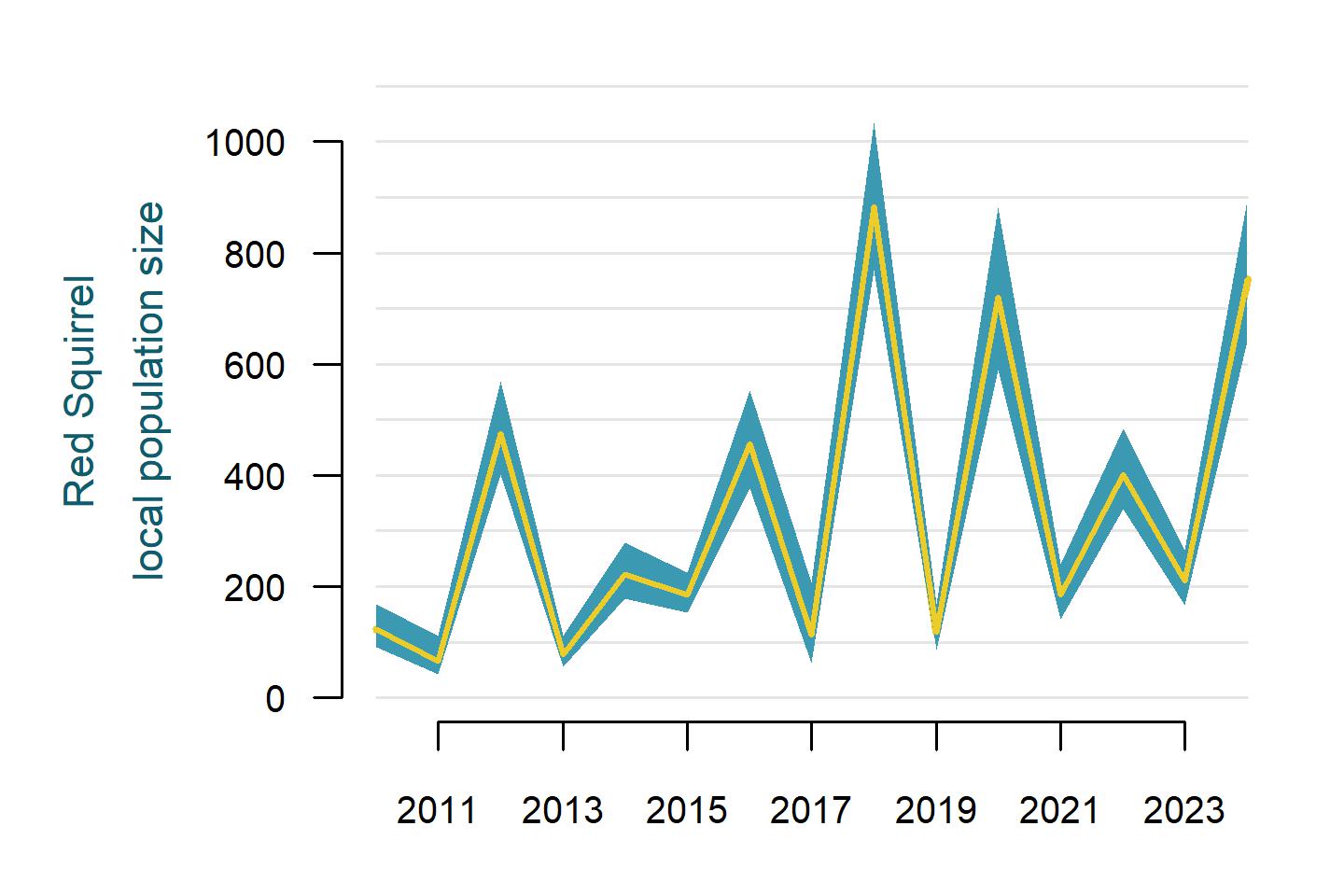

The mean (thick, yellow line) annual estimate of Red Squirrel abundance within the immediate area surrounding all 803 Mountain Birdwatch sampling locations, with a 95% Bayesian credible interval (blue polygon, representing estimate uncertainty).

Since 2010, Mountain Birdwatch protocol has involved recording the number of Red Squirrels at each sampling station with the aim of understanding how this common nest predator’s cyclical population dynamics interact with those of our monitored bird species. Mountain Birdwatch data show a mean annual trend of greater than 9% in the mountains of our region, but thinking of Red Squirrel populations as steadily changing from year to year isn’t a helpful way to describe their population dynamics. The figure above shows a much more complex pattern than a single number can convey. VCE ecologists Mike Hallworth, Kent McFarland, Chris Rimmer (retired) and Jason Hill recently published an open-access paper in Diversity and Distributions describing the population dynamics of Red Squirrel. The conifers on which Red Squirrels feed produce seeds in approximately 3-5 year cycles causing the population to fluctuate significantly from year to year. Red Squirrels can persist in the spruce-fir zone only during winters with substantial amounts of food: namely, mature Balsam Fir (Abies balsamea) and Spruce (Picea species) cones [which mature in the autumn]. In autumns with abundant cones, Red Squirrels are able to move upslope from the hardwood-spruce-fir ecotone, and collect and store these cones in piles (called middens). The collective size of a squirrel’s middens is directly related to their overwinter survival. Following winters with abundant spruce and fir cones, red squirrels remain at those high elevations through the next autumn. During those summers with squirrels at high elevations, squirrels exhibit a substantial effect on the nest survival patterns of spruce-fir birds. In winters without abundant cones, Red Squirrels remain at relatively lower elevations, especially along the hardwood-spruce-fir transition zone.

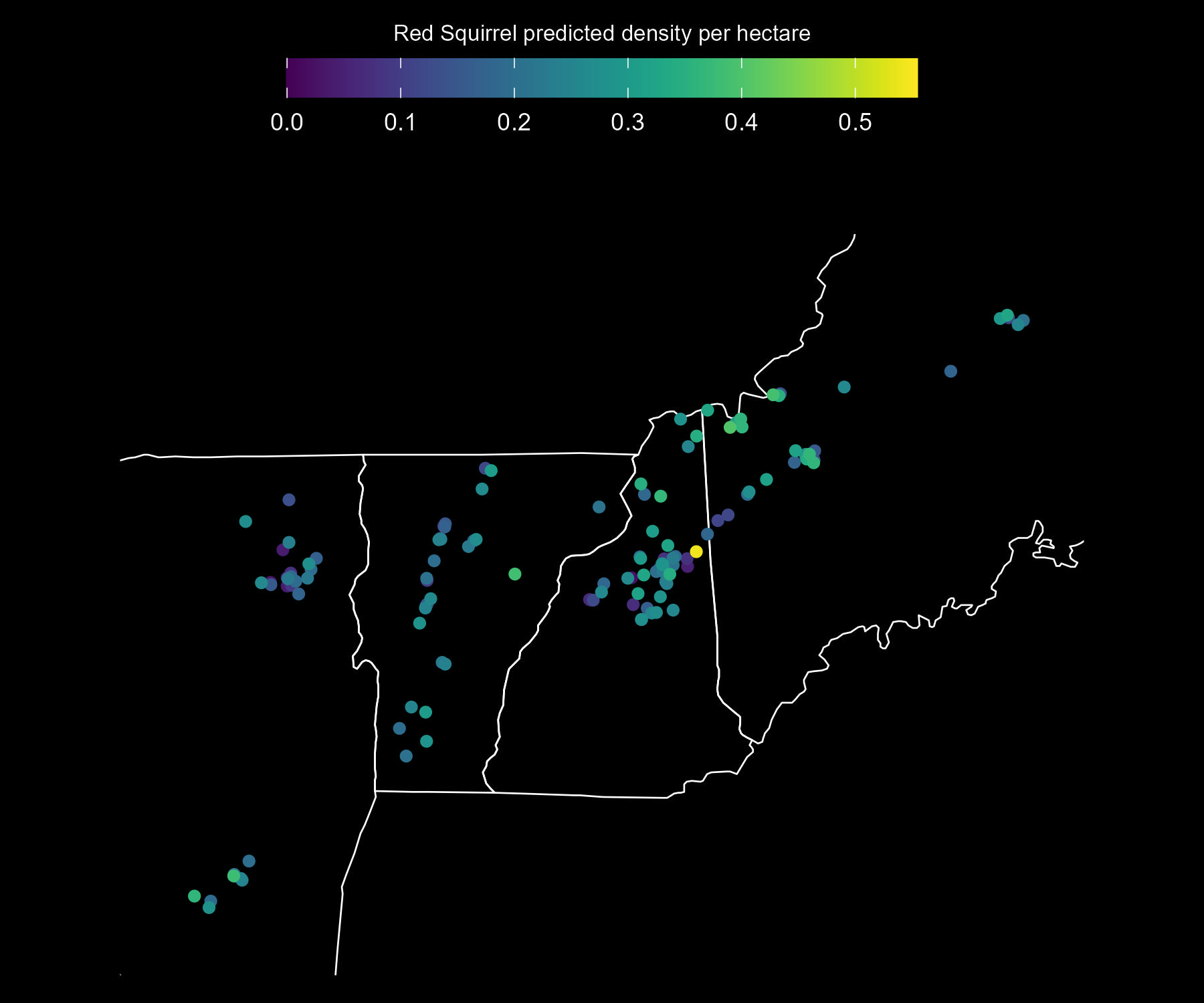

Predicted Red Squirrel adult density per approximate hectare in an average year (between 2010 and 2024), as estimated from Mountain Birdwatch data. The base map shows the extent of the Mountain Birdwatch region: eastern New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and western Maine.

| Region | Mean annual trend (%) | Trend (80% CRI) | Probability of decrease | Probability of increase | Population change (%) 2010-2024 | Population change (80% CRI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All regions | (2.10, 15.95) | 0.05 | 0.95 | 241.06 | (33.77, 693.83) | |

| Maine | (3.04, 17.14) | 0.04 | 0.96 | 289.17 | (52.09, 816.37) | |

| New Hampshire | (1.63, 15.53) | 0.06 | 0.94 | 221.35 | (25.49, 654.79) | |

| New York (all regions) | (1.39, 15.44) | 0.06 | 0.94 | 214.10 | (21.25, 646.36) | |

| New York (Adirondacks only) | (1.51, 15.62) | 0.06 | 0.94 | 219.58 | (23.29, 662.75) | |

| New York (Catskills only) | (0.31, 14.72) | 0.09 | 0.91 | 178.15 | (4.37, 583.43) | |

| Vermont | (2.19, 16.31) | 0.05 | 0.95 | 250.53 | (35.41, 728.83) |

For more information see: Hallworth, M.T., A.P.K. Sirén,, W.V. DeLuca, T.R. Duclos, K.P. McFarland, J.M. Hill, C.C. Rimmer, and T.L. Morelli. 2024. Boom and bust: the effects of masting on seed predator range dynamics and trophic cascades. Diversity and Distributions 30: e13861. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ddi.13861?af=R